Category Archives: Uncategorized

film for front page

Siegal Summer Institute 2016

From Left Back to Right Front: Back row: Jen Glaser, Marla Wolf, Deborah Morosohk, xxx, Sandi Intraub, Susan Morrel,; Middle Row: Elissa Chanales, SArah Alevsky, Elena Levitt, Feygi Phillips, Daniella Botnick, Yehudit Kanfer, Monica Glina, Ariann Weitzman, Howard Deitcher Front row: Sarah Alevsky, Erica Allen, Sam Eisner, Bryan Conyer, Beth Mann. Also present were: , Elena Levitt, Benjamin Barnett, Susan Simon, Feygi Phillips, Charles Stone.

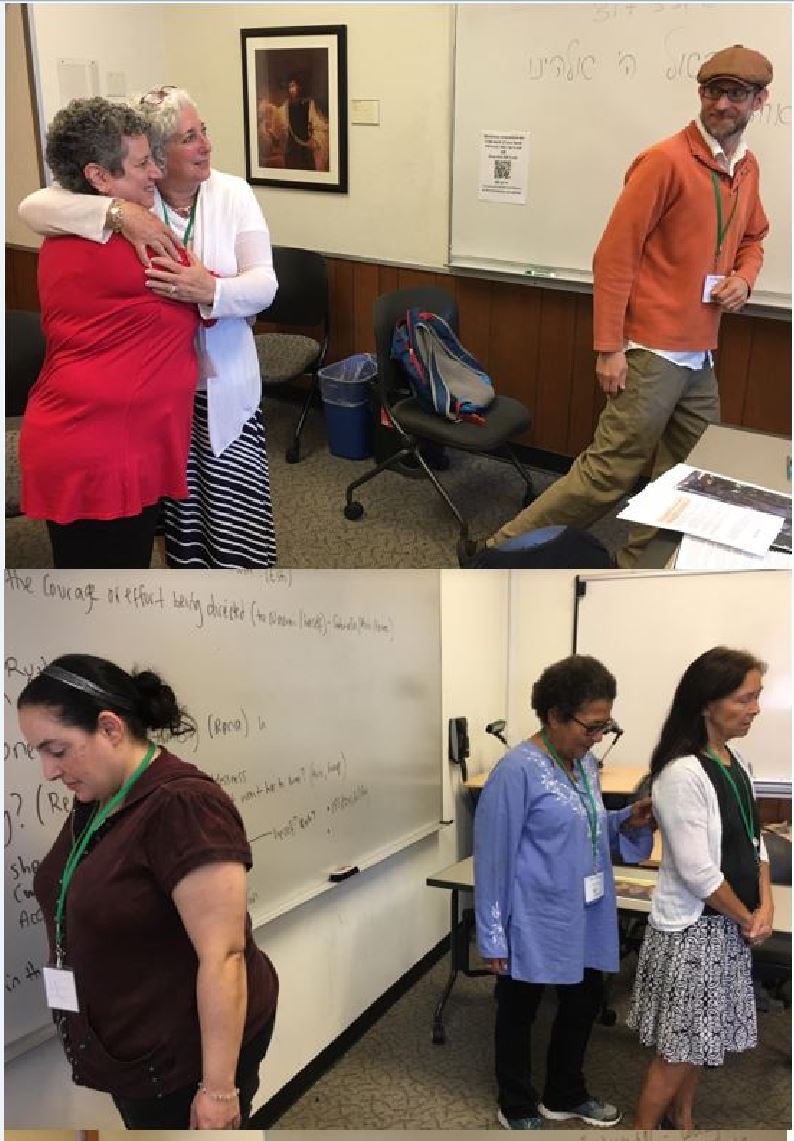

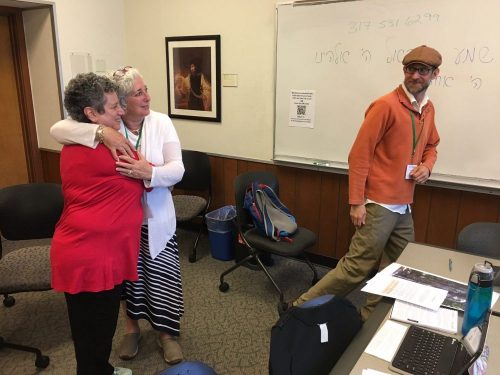

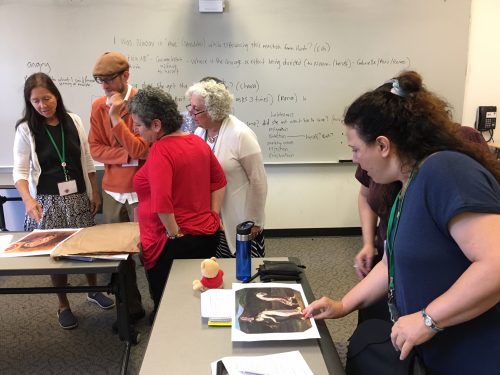

PIJE at Siegal Life-long Learning, Summer Institute, July 2016

19 Jewish Educators came together at the Siegal Summer Institute at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland OH for Beginner and Advanced seminars in Philosophical Inquiry in Jewish Education in July 2016. Participants came fromn Boston, Baltimore, Cleveland, Michigan, Minneapolis, New Jersey, New York, Oakland and even Melbourne, Australia! The Beginner’s workshop was led by Dr. Howard Deitcher and Susan Simon, and the Advanced seminar by Dr. Jen Glaser.

Professional Development Opportunity – Bay area

Save the dates!

Studio 70 in partnership with Engagingtexts will be offering a 4 day workshop in Philosophical Inquiry in Jewish eduation in August (2days Aug. 2nd&3rd + 2 days Aug 10th&11th). These dates open up the workshop to peple coming to

NewCAJE – New Sessions on Hanuka

Truth and Meaning in the Hanuka story

(for Middle and High School students)

Using Philosophical Inquiry to Explore Question of Truth and meaning

in the Hanuka Narrative

Hanuka is a complex holiday, carrying many messages. Its historic roots are documented in various sources, yet these sources convey different information and explain the rituals of the holiday in different ways. For many children, the story of Hanuka is interwoven with the ‘miracle of oil’ through a narrative of the victory of the Maccabees over Antiochus’s army. By middle school many students are questioning what to make of this miracle and the ‘truth’ of this historic narrative. Often, we as educators, leave them to address this question of truth on their own. This lesson seeks to explore the question of truth head on. The focus here is not on teaching the story of Hanuka (indeed it presumes Middle School students know the basics of this story), rather, it offers a philosophical exploration of the concept of truth in a way that is accessible to Middle School youth. The aim of the lesson (or series of lessons) is to offer students a more sophisticated understanding of the notion of truth so that they may have more complex cognitive resources available to them through which to make meaning of this holiday.

These lessons explore the concept of truth in general, and truth in relation to the holiday of Hanuka in particular. The session is designed for Middle and High School students. The lessons are inquiry based. Students will mostly be working in groups then coming back to share and discuss further in a larger group together.

To access the full lesson plan click here

To access the resources used in the lesson plan click on the icons below

(N.B. both Word and PDF versions are provided so that you can adjust the resources to your students if necessary)

- A short story called: “A True Story” and discussion guides

- A source sheet on the narratives of Hanuka

- A final worksheet: ‘Where do I stand’: truth and meaning in Hanuka’

|

Ideas behind this approach to Jewish education? The need for meaning centered education:

Yet figuring out who we are and how we ought to live cannot be done in isolation from other people. That is to say, ‘Thinking for myself’ is not a solitary activity – it happens through engaging with the voices of others – both voices of other members of our own communities, and the voices that make up the extended conversation of our traditions ‘over time’ – voices within Jewish and Western culture that we are able to engage with through the written word and through the Arts. In helping our students develop their own identities and sense of purpose in community with others we are also building their capacity to create vibrant Jewish communities engaged in the ‘Big Questions’ concerning how we ought to live. Philosophical Inquiry in Jewish Education:

Questions however are the end of a thinking process, not the beginning of one. First we are puzzled by something, something grabs our attention, bothers us or pulls us up short – forming a question that captures this puzzlement is itself hard work! Developing the capacity to find an interest and ask a question is critical to a meaning-centered education, it shifts the pedagogical moment from one of response/reaction to initiation/pro-action. Philosophical Inquiry in Jewish Education combines rigorous exploration of meaning with community building and rich, deep Jewish content knowledge through a pedagogy that enables students to think for themselves as a member of a deliberative community. Group discussion is not only seen as a pedagogy but as the means by which we name, make sense of and evaluate our experience and our ideas. Through creating communities of inquiry, participants engage in collaborative meaning-making. Such deliberation maintains individual autonomy (I must still figure out for myself where I stand on the issues discussed), but places this thinking within a communal context that recognizes human inter-dependence. As a communal activity, cognitive work is thereby integrated with deep attention to building reflective, creative and caring community. This approach to education is midrashic in nature: involving close reading of text, a playfulness and openness to interpretation, along with the understanding that interpretation happens in connection to the thinking of others (both those who have come before us and our contemporaries). Central to this approach is an interplay between the world of the child and the text. This happens through exploring the meaning of key concepts and language as it resonates in the child’s life alongside meanings contained in the interpretative tradition. Discussion guides are offered for this purpose. For example, exploring the concept “Miracle” we might use a discussion guide that asks the students what the word ‘miracle’ means when it is used in everyday contexts such as: Discuss what the term ‘miracle’ means in each of these situations

The point here is not that there is right or wrong answer, a true meaning or a false one – what we are tapping into in discussing these examples is the child’s existing understanding of what this term signifies. To reflect on and articulate the meaning of the term in their existing conceptual scheme. By broadening the range of possible meanings available to our students, we help them develop nuanced meaning-structures through which they are able to interpret their own lives. (My favorite anecdote is about a group of Grade 3 students who were getting ready for a class trip, and the teacher was hurrying them to the bus. One student turned to another and said “What is this, an exodus?” The student had internalized the meaning of exodus and could draw on this meaning in reference to their own life, even if in a somewhat wry manner!) |

NewCAJE -sharing our session on Megilat Ruth

Experiencing PIJE at NewCAJE

The first and last sessions engaged participants in inquiries around Biblical texts. In these sessions we chose to use art in different ways: the first, to create a ‘gallery of laughter’ to trigger an exploration of Sarah’s reaction to the news she would have a child and, in the last session, to explore artists’ interpretations of the relationship between Naomi, Orpah and Ruth in Megilat Ruth. The second session ‘”Beyond the first question” focused on skills of inquiry, whereas the third, longer session, offered an opportunity to explore both the ‘theory behind the practice’ of this approach, including videos from the classroom. 59 educators took part in the sessions, several coming back again and again!

Below we offer you the session on Ruth’s silence in depth, including the materials and lesson plan. If you try it – let us know how it goes by writing in the comments section below!

Interpretations of Naomi’s Silence

Ruth’s famous plea to Naomi to let her come with her is one of the best known parts of the Megilat Ruth – we expect Naomi to be happy, to be touched by this moving speech and reach out to Ruth…. but what really happens next? In the text we are told that Naomi’s response to Ruth is silence:

| יח וַתֵּרֶא, כִּי-מִתְאַמֶּצֶת הִיא לָלֶכֶת אִתָּהּ; וַתֶּחְדַּל, לְדַבֵּר אֵלֶיהָ | 18 And she [Naomi] saw that she [Ruth] was determined to go with her, and she stopped speaking to her |

| …יט וַתֵּלַכְנָה שְׁתֵּיהֶם, עַד-בּוֹאָנָה בֵּית לָחֶם | 19 And they went on both of them, until they arrived to Beit Lechem… |

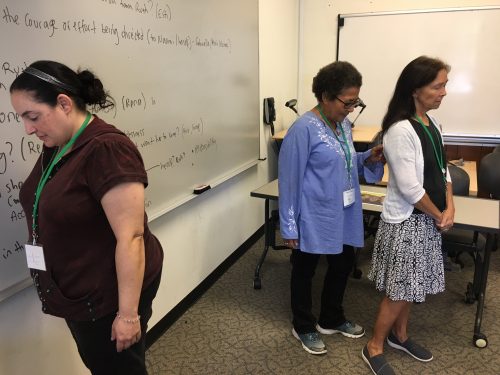

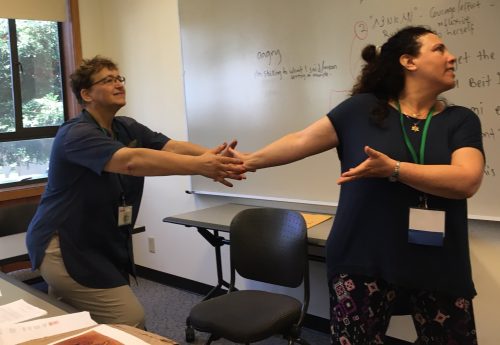

What does it mean to “cease speaking” to someone? (וַתֶּחְדַּל, לְדַבֵּר אֵלֶיהָ). Was her silence a way of giving Ruth permission to come, or was Naomi simply left speechless? Was it a way of stepping back and letting Ruth make up her own mind or does she then just ignore Ruth as each continued the journey in their own space (וַתֵּלַכְנָה שְׁתֵּיהֶם)? What else might it have meant? After exploring our own uses of silence we returned to the text and explored what we thought Naomi’s silence meant as we looked at a range of traditional and modern commentaries, including seven different images of this moment portrayed in art and sculpture. Breaking into groups we then created a ‘freeze frame’ of this moment as we interpreted it. Hold your curser over the photos below to hear how we interpreted the scene!

To access the resources used in this session click here.

To access the lesson plan click here

Place your curser over the pictures below to see what the educators have to say about their ‘still frames’

“Thank you for a meaningful session about Naomi’s Silence. You have so beautifully invited us to read the text from different perspectives. Focusing on Naomi’s silence became an essential detail in my reading the Megilah.” Esti BenDavid

Sample Curriculum

Upper Primary Curriculum Example: lech L’cha

Please click here to go to the Sample Curriculum “Lech L’cha” that is detailed in the following article:

Dr. Jennifer Glaser and Dr. Maughn Rollins Gregory (2016), “Education, Identity Construction and Cultural Renewal: The Case of Philosophical Inquiry with Jewish Bible” in The Routledge International Handbook of Philosophy for Children, eds: Maughn Gregory, Joanna Haynes and Karin Murris : Routledge, UK.

Who We Are

Meet the team behind Engaging Texts

Jennifer Glaser, PhD.

Founder and Director of Engaging Texts.

Jennifer Glaser

Rabbi Dr. Howard Deitcher

Senior Bible consultant to Engaging Texts Network

Dr. Deitcher works on the development of curriculum, leads professional development seminars, and engages in strategic thinking around the development of the Engaging Texts network. Dr. Deitcher is a senior lecturer at the Melton Centre for Jewish Education at the Hebrew University and its former director. He is the current educational director of the Revivim Program at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, training students to teach Bible in Israeli national secondary schools. Dr Deitcher spent a sabbatical year working with Professor Gareth Matthews in schools and has been active in the field of Philosophy for Children for over 25 years.

Professor Maughn Rollins Gregory, J.D., Ph.D.

Senior consultant to the Engaging Texts Network

Maughn Gregory is a senior consultant to Engaging Texts, collaborating around the articulation its theoretical conceptualization, developing evaluation tools, and taking part in professional development workshops. He succeeded Matthew Lipman as the director of the Institute for the Advancement of Philosophy for Children at Montclair State University – the world’s oldest organization devoted to young people’s philosophical practice. Gregory is a Professor of Educational Foundations at Montclair. He publishes and teaches in the areas of philosophy of education, Philosophy for Children, pragmatism, political philosophy, gender, Socratic pedagogy and contemplative pedagogy.

Benjamin Barnett

Web developer and Webmaster, Engaging Texts

Benjamin Barnett is co-owner of media schmedia LLC. He and his wife / business partner, Halle, provide branding, marketing, and web design services for small businesses, non-profits, educators, artisans, and other small-but-beautiful ventures throughout greater Cleveland, across the US, and around the world. Benjamin is also a volunteer educator trained in Philosophical Inquiry. He facilitates a group of 5th-7th grade students in an ongoing Philosophical Inquiry with Parshat Hashavuah on shabbat mornings at Kol HaLev, Cleveland’s Reconstructionist Jewish Community.

Meet Engaging Text’s Partnerships

Jewish Education Center of Cleveland

Judith Schiller

Coordinator of Philosophical Inquiry in Jewish Education at the JECC,

Shoolman Graduate School of Education, Hebrew College

Rabbi Alvan H. Kaunfer

Coordinator of Philosophical Inquiry in Jewish Education at the Shoolman Graduate School of Education, Hebrew College.

Rabbi Kaunfer is Director of the Congregational Education Initiative at Hebrew College and is working in close partnership with Engaging Texts in developing Boston as a regional hub for advancing Philosophical Inquiry in Jewish education. Rabbi Kaunfer served as a Rabbi at Temple Emanu-El, Providence for 25 years. He was also the founding Director of the Alperin Schechter Day School in Providence, which he headed for 13 years. He is a graduate of Brandeis University, Teachers’ College of Columbia University, and was ordained at the Jewish Theological Seminary, from which he also holds a Doctoral degree in Education.

Over 70 Leading Educators and Jewish Professionals